The Hidden Costs Of Haiti's Revolutionary History by Ilana Jael

[Updated 4/10/2023]

If you don’t happen to be familiar with Haiti’s history, there are a few references in our upcoming production of Cry Old Kingdom you may find a bit perplexing. Who, for example, were Toussaint L’Ouverture, Dutty Boukman, and Georges Biassou? Why does Edwin refer to the Haitian people as the “descendants of slaves?” Who is this fearsome “Duvalier” figure the characters are referring to, and how did he gain his power over the Haitian people?

While I obviously can’t aspire to describe the entire history of a nation in the scope of a single blog post, I do hope to help provide some context to the play by providing a basic overview, starting from the very beginning. In fact, the earliest recorded history of what would become Haiti as we know it began when Columbus landed on the island in 1492, finding there the indigenous Arawak people on what they called “Ayiti,” which means “mountainous land.”

Landing of Columbus by John Vanderlyn, 1846

However, the impact of disease and colonization practically decimated this population of early natives, and after a 200 year period in which Haiti was controlled by the Spanish, the country was seized by the French in 1659. They named the territory Saint Domingue, which became for a time the most lucrative colony in the world.

But these profits would come at an incredibly high human cost—the cost wrought by slavery. This economic system was established by the French owners to supply their plantation system. They imported around 800,000 Africans to the colony, taking them as property and forcing them into labor. Those who were enslaved lost even their basic rights and liberties, and would be tortured and killed if they tried to escape.

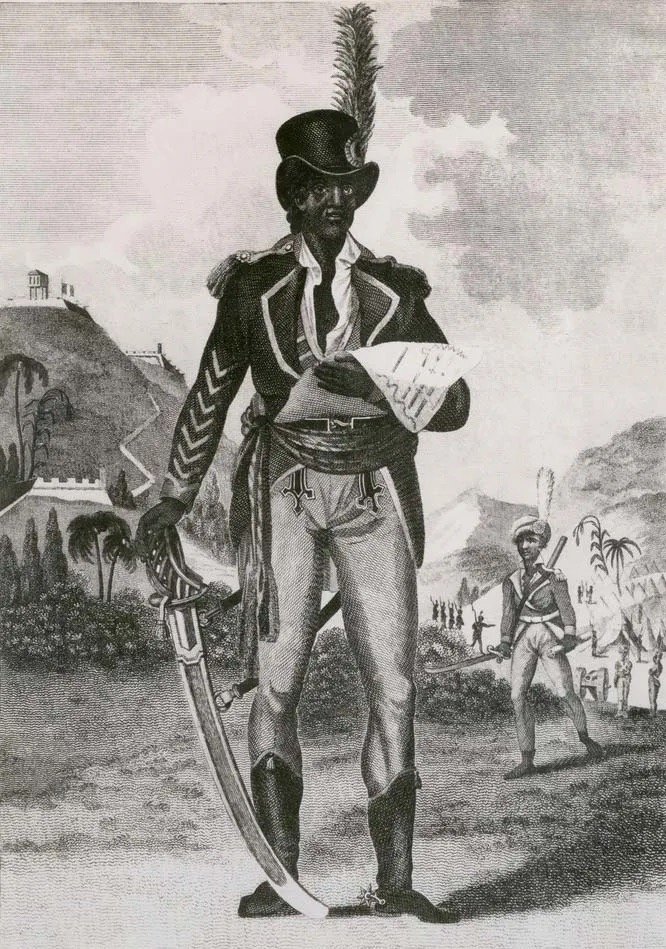

Artist depiction of Toussaint L’Ouverture

Along with the precedent set by the French and American revolutions, the injustice of these circumstances would serve to inspire the Haitian Revolution, described as “the largest and most successful slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere.” This is where Toussaint L’Ouverture, Dutty Boukman, and Georges Biassou come in; all were leaders of this noble war, the celebrated fathers of the proud nation that emerged.

After an initial uprising in 1791, conflict raged until 1803, when French forces were finally defeated. The nation declared independence on January 1, 1804, making Haiti the first black republic in the world and allowing it to serve as a “powerful symbol of black liberation and racial equality, a harbinger of African emancipation, and a beacon of hope for the anti-slavery movement.” Another revolutionary leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, became the first ruler of the new independent nation, presiding as “Emperor of Haiti” until he was assassinated in 1806.

However, this groundbreaking victory came at a cost, both literally and figuratively. In 1825, France forcefully demanded monetary reparations from the new country for the loss of their former colony in the form of 150 million francs, equal to $21 billion in today’s currency. This enormous cost severely hampered the country’s economic development, which is thought to be one of the reasons the nation remains impoverished today.

Another is Haiti’s subsequent diplomatic isolation: because other nations, including the US,

feared that the successful Haitian revolution would spur similar rebellion in their slaves, Haiti was perceived as a threat and treated accordingly, with continual negative attitudes for the country also seeming to have been fueled by racism. In fact, it was not until 1862, after slavery was finally abolished in the United States, that Abraham Lincoln finally recognized Haiti as an independent nation at all.

These external influences, combined with the fraught political and racial dynamics described earlier led predictably to internal chaos, and Haiti was subsequently presided over by a series of unstable governments, going through more than 50 rulers in the following century. Though the US occasionally attempted to intervene to stabilize the struggling nation, this was chiefly to protect their own economic interests, and generally had counterproductive results.

Most notably, in 1915, an invasion by US Marines led to a 20 year occupation of the country that was marked by further human rights abuses for the Haitian people. In a practice called corvée, Marines forced peasants to work on the roads they were building without pay, while also committing brutal crimes—including the rape of Haitian women— and receiving no punishment.

Most chillingly, 6,000 Haitians who participated in guerrilla revolts against these invaders were ultimately slaughtered, including revolutionary leader Charlemagne Péralte, who remains a powerful symbol of Haitian resistance.

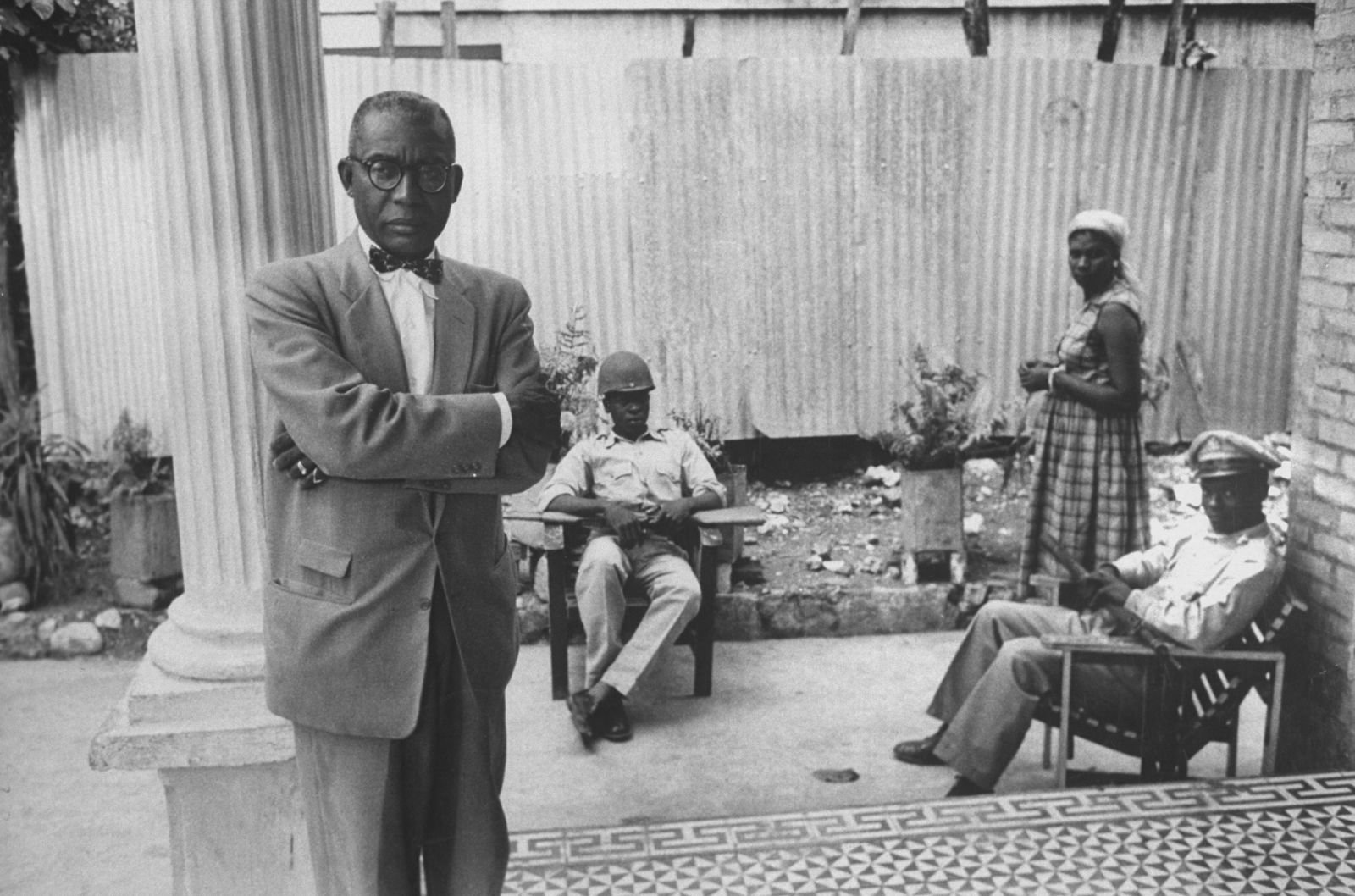

Francoise Duvalier in May, 1957

Aside from this outright violence, the occupation also worsened the existing resentment between races as whites and mulattos were favored by the foreigners while darker skinned Haitians were condescended to and disdained.

Notably, this occupation took place during Duvalier’s youth, and likely influenced the radical beliefs he developed in response. During its final years, he joined a group called the Griots and adopted an ideology known as noirisme, described in one article as an “anti-liberal and anti-Marxist political and cultural ideology that equated authentic Haitian identity with blackness.”

As explained in another source, Duvalier then went on to study at the University of Michigan Graduate School of Public Health as part of a program to defeat an infectious skin disease called yaws that was incredibly prevalent in Haiti. The infection is easily treated with penicillin, which Duvalier would then go on to provide to the masses, leading to the (temporary) near eradication of the disease.

This, in turn, gained him incredible favor in the eyes of the Haitian people, even taking on a mystical dimension as some Haitians attributed this development to magical powers held by Duvalier as opposed to a miracle of modern medicine. This, combined with the populist appeal of his “noirisme” beliefs to a black majority tired of being downtrodden resulted in his successful election to the presidency in 1957.

But signs of trouble quickly emerged after Duvalier became head of state. His enemies began mysteriously “disappearing,” and he took actions that effectively eliminated free speech, banning rival political parties and shutting down any newspaper that dared criticize him. Matters only worsened after an attempted coup launched in 1958 by three exiled Haitian army officers and five American mercenaries; though the attempt was easily defeated, it tremendously worsened Duvalier’s paranoia about being overtaken.

TJ Pursley plays “Henri” in New City Players’ production of Cry Old Kingdom

His distrust of the Haitian army also led him to form his own militia to protect him from his own forces. Nicknamed the Tonton Macoutes, after a mythological bogeyman known for kidnapping and devouring naughty children, these ruthless assassins are thought to be responsible for the murder of between 30,000 and 60,000 Haitians.

Though the extent of this violence seemed arbitrary to some, leading them to question Duvalier’s mental stability, it seems as if it was in fact part of a reasonable if brutal strategy on the leader’s part: one that primarily served to shore up his power at all costs. Targets were not only those whose opposition to the regime posed any real threat, such as journalists and political influencers, but any civilians overheard making the slightest criticism of the leader. Female offenders were sometimes raped rather than slaughtered to intimidate them into silence, and the families and even the children of those who were deemed dangerous were often killed or tortured as well.

As this violence raged, material conditions for most Haitians also notably worsened as Duvalier took hold of the country’s resources, leading to food shortages and widespread malnutrition. The situation was so dire as to push many Haitians away from the country entirely. Better-off professionals who had the means fled through conventional avenues like air travel, which in turn worsened the collapse of the educational and healthcare systems. And many of those without such options instead took the desperate option chosen by Henri in the play: choosing to risk their lives to flee to America in dangerous makeshift boats rather than staying and facing such a limited life, which led this diaspora to be described in the lands they arrived as “boat people.”

In 1964—the year the play takes place—Duvalier has just named himself “president for life,” after holding a sham election in which he was the only candidate and all ballots had been pre-marked “yes.” To heighten his influence over the Haitian people and further strike fear into the hearts of anyone who might dare oppose his reign, Duvalier also began to deliberately style himself after Baron Samedi, the vodou God of death, donning clothes traditionally associated with the figure and even changing his voice to match his nasal tone.

The Tontons Macoutes and a Haitian child.

And though this evocation was certainly appropriate for a man whose influence brought grave suffering to so many, even he wasn’t immune to the realities of mortality, and died in 1971. Before doing so, he transferred his “president for life” title to his son, Jean Claude Duvalier—who ultimately proved to be just as brutal and ineffective a leader as his father.

Though some of those who have ruled in Haiti since have attempted to govern in a more sensible manner, the distrust wrought by the Duvalier years has made it incredibly difficult for any more stable government to form, and the country remains plagued by political and economic woes. Both emotionally and materially, the country has yet to fully heal from the wounds wrought by this dark period, and, more to the point, from the even deeper fissures wrought by slavery, racism, and a centuries-long history of oppression.

Thus, while revisiting this dark period in our production of Cry Old Kingdom may be painful for some, we at New City Players are also hopeful that it may help increase understanding of it, and thus between Haitian and non-Haitian community members. Meanwhile, though the migration of immigrants out of Haiti may have been driven by unfortunate circumstances, we can still make an effort to appreciate the beauty of the communities that they created in their new homelands, including in our very own South Florida. For more insight into Haitian art, culture, and history, stay tuned for our next blog!

Cry Old Kingdom

by Jeff Augustin

Directed by Marlo Rodriguez

Haiti, 1964. Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s repressive regime has forced once-successful artist Edwin into hiding, turning him into a walking ghost. When Edwin finds a young man building a boat to escape to America, and persuades him to pose for a painting, he finally feels alive again. But with cries for revolution resounding through the nation and the regime’s death squads on the prowl, no one’s life is safe. Sometimes trying to dream and survive forces impossible choices.

WHEN

April 13-30, 2023

WHERE

Island City Stage

TICKET PRICE

$20-35